Alla Prima Amnesia

Phoebe Helander’s paintings at P·P·O·W

Published in The Ridge Review on December 15, 2025

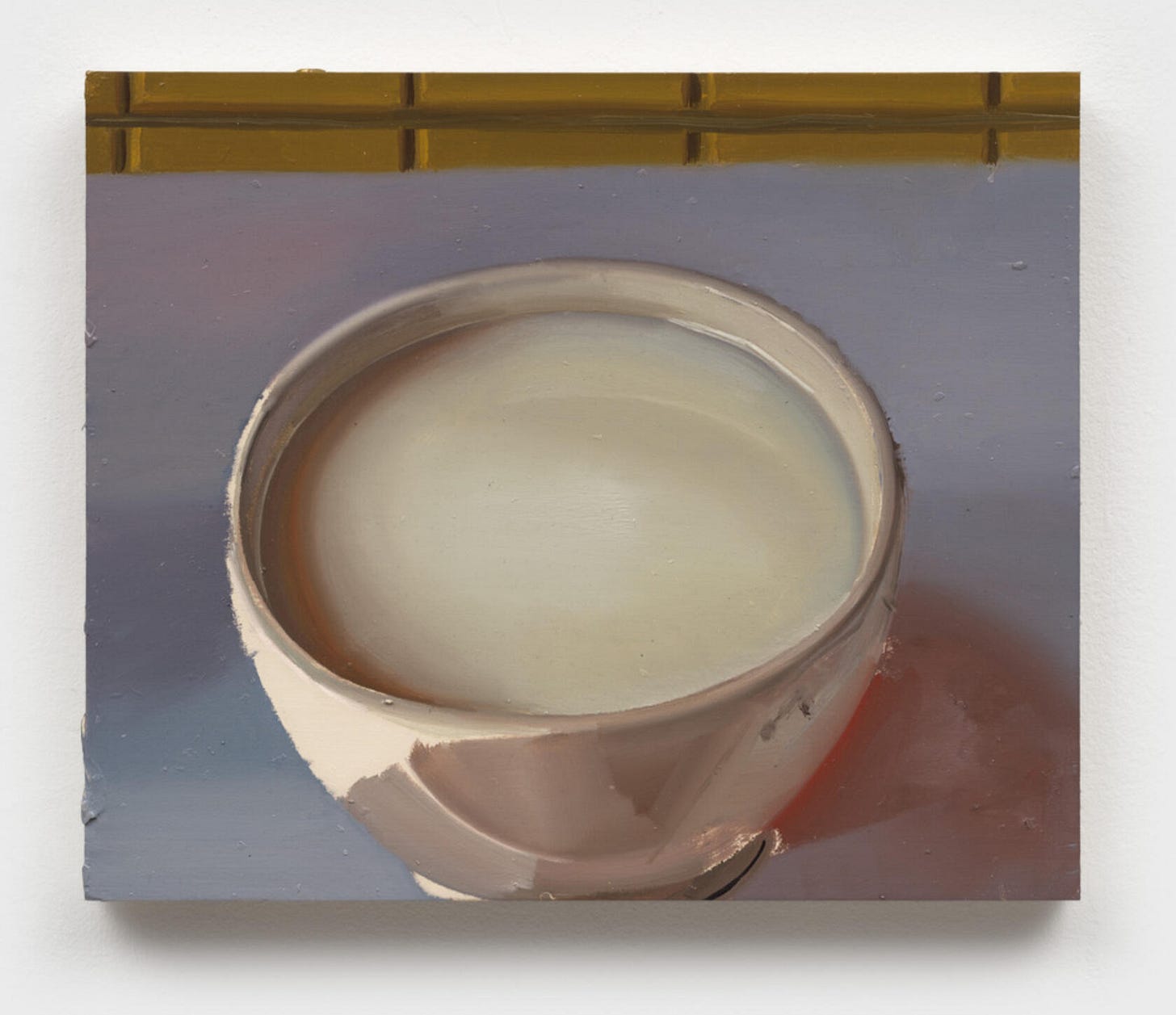

Phoebe Helander, Bowl of Milk III, 2025. Oil on wood, 11 1/4 × 13 1/2 inches.

There must be over fifty paintings in Phoebe Helander’s Paintings from the Orange Room at P·P·O·W. All are still lifes, approximately head-sized. Most are painted on uncradled slabs of wood, some of which have already begun to warp or split. The panels appear to be prepared hastily and en masse, their edges splintered and striped with drips of gesso.

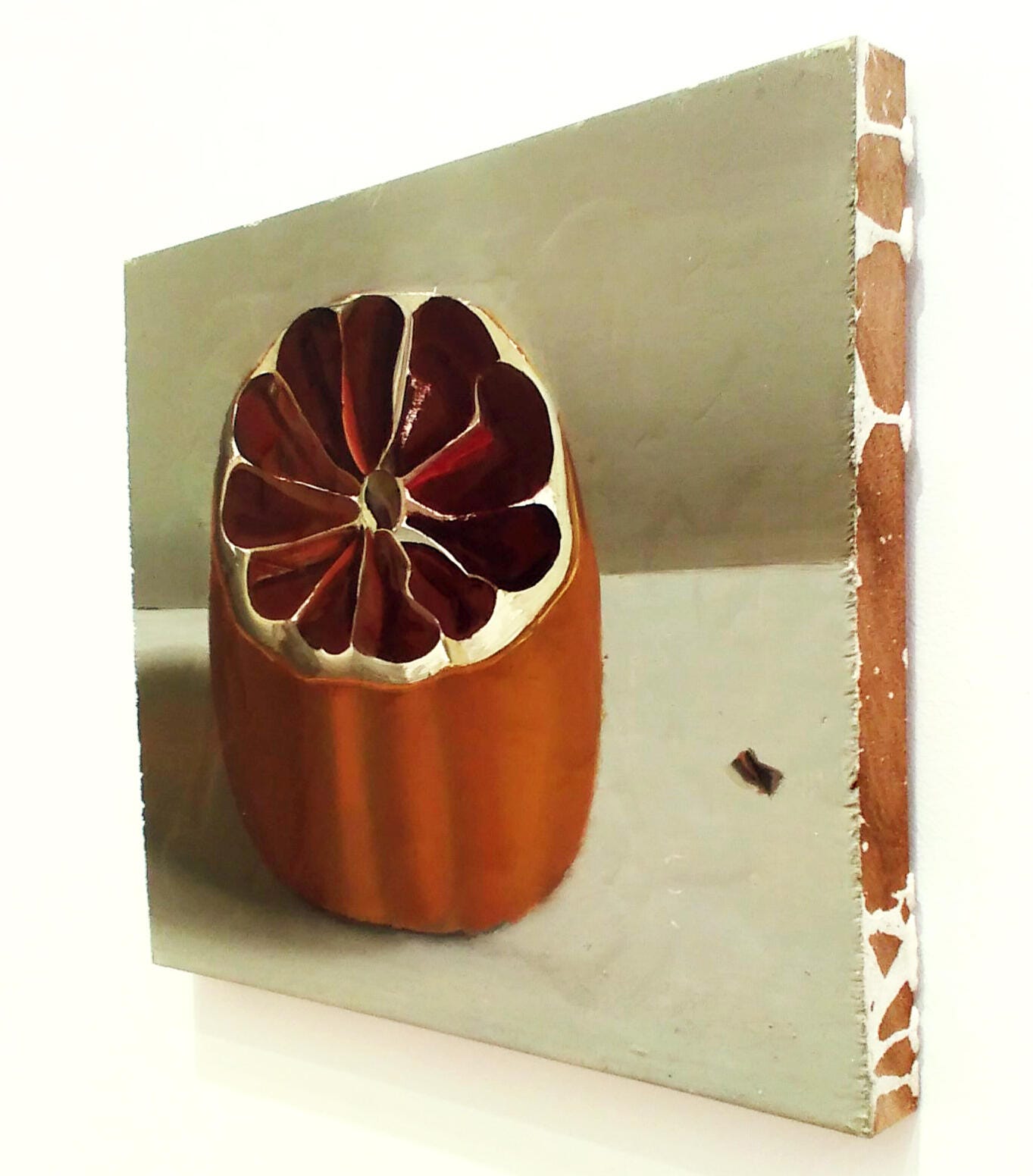

The paintings are nice, even refreshing, compared to the other painting shows on view in the area. The lack of preciousness evident in the panel preparation contrasts with the careful representations of familiar still-life objects while accentuating the materiality of the painted images. In the best of the paintings, material support, brushstroke, and represented object correspond, synthesizing present and re-presented objects (painting and still-life subject). In these works, the close-looking of observational painting is materialized, asking for and rewarding the same type of close-looking on the viewer’s part. The white lines separating the segments of a lemon echo the drips of primer down the sides of the wood slab. A crack in the wood panel creeps across the representation of a fallen red glass, as if the cup’s fragile surface too threatened to split. The wrinkled surface of unevenly dried paint acknowledges the passage of time while representing a momentary quiver in a bowl of milk.

Phoebe Helander, Cross-Section of an Old Lemon II, 2025. Oil on wood, 11 1/4 × 13 inches.

This synthesis, however, happens in only a few of the paintings in the show. The many others land in the comfortable realm of alla prima still life—fine enough (for decoration). But the paintings claim to do more (or, rather, their maker claims they do in the show’s accompanying essay and press release): to bear witness to change and instability in a world that quantifies, sensationalizes, and advertises. But although painted in front of wilting bouquets and burning candles, flower and flame alike may well have been painted from photograph, so stable and unproblematic are Helander’s finished paintings. There is nothing inherently wrong with paintings that take on the quality of photographs. But we do not see like cameras. And Helander’s commitment to durational six- to ten-hour alla prima painting sessions of changing objects, to perception beyond the screen, more often than not results in photographic images, so that the process is only discoverable in her writing (by turning our attention away from the works to read an explanation of them):

“So I end up continually painting over my work, re-making the same central area of the composition, for as long as the candle burns. Loss is a natural part of change, and that’s something I accept as a part of this work. My goal is to stay with the flame.”

A nice idea. But paintings are ideas materialized. And the idea is not materialized in most paintings in the show.

Paintings are static, visual objects. To materialize loss, a painting must contain what was before—it must reveal its own history visually. Such a commitment to durational attention as Helander’s, if it is to become art and not simply a token of her personal meditation (for what could we viewers learn from the latter?), must solve the formal problem of how to embody the phenomenological experience of an object that is three-dimensional and temporal by nature in the two-dimensional and static medium of paint. This problem was not solved, once and for all, with Cubism, or Futurism, or any other Modern -ism. It remains the problem of each painting today. How do we represent the world when we are habituated (addicted) to having screens and algorithms pre-process experience for us?

Contrary to Helander’s “staying with the flame,” the kind of attention that is the antidote to the doomscrolling, ad-riddled, ADHD-inducing addiction of contemporary life is not the mere presentness of sense certainty, for which this-here-now is all there is and is gone as soon as it is. Such is the ahistorical presentness of the amnesiac. A productive presence of mind would rather be a type of attention that brings its past forward with it: a presentness with a historical consciousness that is aware that the material it encounters is informed by what happened before—whether the wax formations of a melting candle, a prior brushstroke by one’s own hand, or the historical genre of still-life painting—and is the ground from which the future develops. The real problem is how to cultivate presence of mind while committing to what came before and what comes after: a problem that painting alla prima may not be able to tackle with its limit of working only while the paint is wet. What happens when Helander commits to the same painting day after day? Month after month? The solution would perhaps not be so fresh, so nice, so many (so potentially profitable). I venture to think that such an undertaking might be appealing to Helander, given the values she articulates in her essay and her attraction to materials that change over time (pools of medium-rich paint that will wrinkle as they dry, warping supports that will crack the paint film).

That most of Helander’s paintings don’t go beyond a way of seeing habituated to a pre-processed, flattened image taken by a mechanized cyclopic lens, is understandable given the nature of her undertaking. The formal-material problem she has set herself, which requires overcoming deep conventions of how we see today, is vast enough to devote a life to. The three or four paintings in the show that hint at a solution to the problem are promising steps for further inquiry. That the show at large doesn’t go beyond an Instagram-like glut of images, turning the three-room gallery space into a kind of feed in which the viewer circumambulates instead of scrolling through images packed too close to each other, however, undercuts the project. The painter’s commitment to this problem would be more convincing had the forty-six or -seven other paintings been left out. The success of this project would entail that each painting asks a viewer to look at it with the same degree of effort and attention that was put into it—an impossible task in a space packed with fifty paintings and nowhere to sit.

Phoebe Helander, Cross-Section of an Old Lemon II, 2025. Oil on wood, 11 1/4 × 13 inches.

Phoebe Helander, Paintings from the Orange Room, P·P·O·W, 390 Broadway, 2nd Floor, October 31 - December 20, 2025

I’m starting to think that the honor of making capital-P Paintings will be awarded to very few, and very similar painters! It’s really not a surprise that Phoebe falls short of such a bruising, cerebral expectation of what a painting should be.

Let me start with the author’s last paragraph. There is actually nothing stopping the author from putting a high degree of effort and attention into viewing the work. The author could (probably) bring their own chair in, make multiple visits, or ask to view works in private. We actually live in the freest time to experience paintings that ever existed. But of course, paintings don’t need to be encountered this way in order for real connection and meaning to be gleaned. The nice thing about a painting is that it doesn’t need to express every truth or formal-material connection in one canvas.

After a nice introduction of the work, much of this writing has to do with the supposedly ahistorical “amnesia” of the paintings. I seriously doubt that Helander (with the educational baggage that comes from a BA from Hampshire College and an MFA from Yale) is capable of being ahistorical or an amnesiac of any sort. In fact, the crush of history and of the present clearly defines her motives in her essay. Is there something about her brushwork, color, or composition that supports the author’s claim that the paintings fail to “materialize loss”? If so I would love to hear more, because formal, concrete observation is lacking after the start of the review. The author all but says that alla prima painting is inadequate for conveying contemporary meaning, which I take many issues with. Other critics (https://hyperallergic.com/phoebe-helander-paints-objects-in-time/) were able to pick out transcendent moments from this painter working with this kind of narrowed attention.

The parenthetical “(for what could we viewers learn from the latter?)” might be the split in the road between my views and that of the author, who I deeply respect. Thank you for writing!

I always enjoy your writing about art, and often apply some of your principled judgments to looking at your own work. And sometimes mine! I appreciate what you have written here, and also the paintings I've seen from the show online.

Having been a journalist for 20-odd years, I found what I would've used for the headline in your last sentence: "50 paintings and nowhere to sit." I felt a lot less alone when I read that. Well done, Anna.